Application Services Best Practices

Application services are an integral part of popular layered architectural styles, such as ports & adapters (hexagonal), onion architecture or clean architecture.

In this post I suggest some quick design guidelines to improve the design of your application services.

⦁⦁⦁

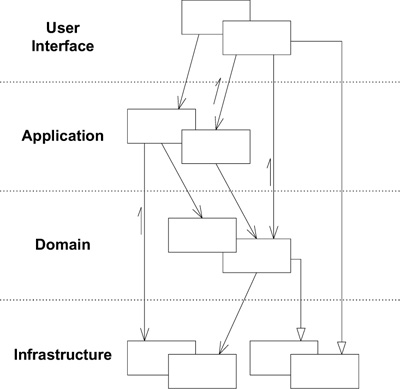

Separating the code in your project by concerns simplifies maintenance (e.g., understanding/reviewing, fixing bugs, upgrading dependencies) and evolution (e.g., adding features). At least three kinds of concerns (or layers) are generally accepted:

- presentation (user interface)

- application (sometimes divided into application and domain)

- infrastructure

|

| Layers as presented in the Domain-Driven Design book |

They manifest themselves as layers in your architecture (or, actually, in a module view of your architecture). In the end, these layers become packages or folders in your app (depending on your language, naturally).

Application is where your code is. It’s where your “business rules”, however you decide to implement them, are. In more complex systems, it is usually worthwhile to break this layer further into two: application and domain. More on that later.

Presentation is where you put all code that converts requests from the “outside world” into the internal representation you application requires. For instance, a REST presentation layer is composed of endpoint controllers that would receive HTTP requests and parse them into objects. Next, this layer would call the appropriate application layer method and (maybe) await for a response. If there’s a response from the application, the presentation will convert it to whatever content format the HTTP request needs and send it back to the client.

Infrastructure is where you put everything else. Utility classes/functions, plumbing/platform code and whatnot.

Application vs Application + Domain

As stated, we can further separate application code into two distinct modules application and domain. When doing this separation, the actual business rules go into the domain layer and the application layer becomes responsible for the coordination code (aka application or use case code). In other words, the latter contains what your app can do and the former organizes how your app does things.

Why use case code? In the end of the day, each method of an application service will represent a coarse-grained (or high-level) operation (a.k.a. use case) your application can do. For instance, consider the application service below:

@Service

class UserAppService(private val userRepository: UserRepository) {

@Transactional

fun upgradeClass(userId: UserId /* Long */, newLevel: UserClass) {

// implicit "begin transaction" by @Transactional

val user = userRepository.find(userId)

val upgradedUser = user.upgradeClass(newLevel)

userRepository.save(upgradedUser)

// implicit "commit transaction" by @Transactional

}

}

To “upgrade a user’s class” (whatever that means to the business) is a user case of the application.

Application services have many, but specific, responsibilities. In this article I’m going to lay down a quick list of good practices for these services, which are the most important objects that live in the application layer.

Make them thin, they should not contain heavy logic

The application layer is the integration layer. This means it can only be tested via (expensive) integration tests. A good practice, then, is to keep the logic here to a minimum, and push whatever possible to other layers (such as infrastructure or domain).

For instance, considering the application service method presented before:

fun upgradeClass(userId: UserId /* Long */, newLevel: UserClass) {

val user = userRepository.find(userId)

val upgradedUser = user.upgradeClass(newLevel)

userRepository.save(upgradedUser)

}

In this form, it potentially only requires one test, since there are no “logical branches”. Conversely, if it were like:

fun upgradeClass(userId: UserId /* Long */, newLevel: UserClass) {

val user = userRepository.find(userId)

val upgradedUser = if (newLevel == UserClass.PLATINUM) /* do something */ else /* do something else */

userRepository.save(upgradedUser)

}

Then now you are required to create at least two different tests to verify this method properly.

Naturally, the application services should not contain domain logic, but application logic, only.

Separate their steps

Application services methods generally contain a very specific sequence of steps in the format “hydrate” -> “execute” -> “dehydrate”. More specifically, they typically do the following tasks, in the sequence:

- Open the transaction

- Hydration

- Fetch the entity from the Repository into memory. Here the Repository can be a private database or remote API. They aren’t interchangeable and affect greatly concerns like availability and (distributed) transactions.

- Invokes domain logic (aka methods on aggregate roots)

- Dehydration

- Persists the entities back and emits events

- Close the transaction

Notice, again, these are all “integration” tasks. Therefore they require integration tests to be verified. For instance, you’ll have to have a running database server (or a contract server for the remote APIs) during this test. Just this need alone will add a considerable increase in the time each test will take to run, plus add potential to interference and flakiness.

Avoid branching logic (no ifs)

This is so much an important aspect, that it pays to get dive into a bit more.

The application services are the part of your app that should contain most heavyweight integration logic (such as calling repositories or external services). This means their tests are going to be more complicated, likely integration tests. Therefore:

- The application methods should be straightforward, keeping branching to a minimum

- For instance, without any branches (no

ifs), a single (integration) test will suffice

- For instance, without any branches (no

- If you have logic that implies branching, move them to external (standalone) functions, and test them in isolation. This allows you to test these with unit tests, which will make it easy to test all logic branches.

To be continued…

Leave a Comment